On April 2, 2025, after weeks of speculation and heightened

geopolitical tension, President Trump announced sweeping global

tariffs on what he dubbed “Liberation Day”. The tariffs

included a baseline universal tariff of 10% on most imported

foreign goods,1 in addition to specific “reciprocal

tariffs” on several major trading partners. It was initially

announced that the universal tariff would go into effect on April

5, while the reciprocal tariffs were due to begin on April 9.

However, on April 9, 2025, Trump announced that most of the

reciprocal tariffs would be delayed for a period of 90 days.

As the global community grapples with the ramifications,

companies are urgently assessing the impact on their operations and

supply chains.

In this article, we provide a snapshot of the latest key tariff

changes, reactions from major trading blocs, and we explore some of

the immediate steps companies should be

considering.2

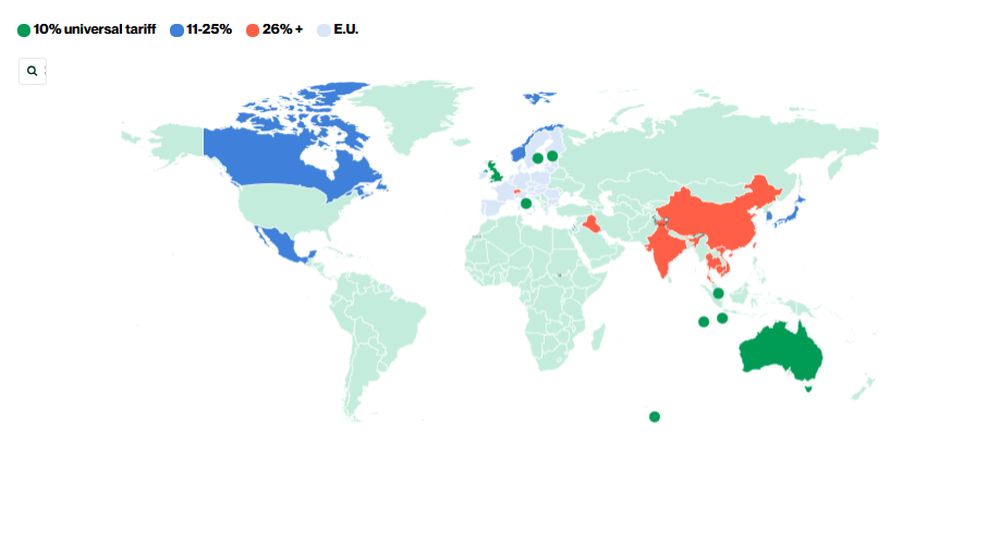

Snapshot of tariff changes

Below is a summary of some of the key tariff changes recently

announced by the U.S.

All countries are currently subject to a 10% tariff until the

90-day pause window ends in July, at which point the tariffs are

set to increase to the “Liberation Day” rates. Notably,

the new tariffs will not apply to products already subject to

tariffs, including steel, aluminum, automobiles, and parts. Also

exempt are products such as copper, pharmaceuticals,

semiconductors, lumber products, gold bullion, energy and minerals

that are not available in the U.S., and most recently (in respect

of Reciprocal Tariffs), smartphones, computers, and certain other

electronic devices and components (although, this appears to be

subject to change). Nevertheless, the White House has identified

additional products and sectors that merit further investigation,

including pharmaceuticals, semiconductors, and certain critical

minerals. This may lead to tariffs targeting these sectors.

*Canada and Mexico were deemed exempt from the “Liberation

Day” tariffs because they were already facing 25% tariffs,

imposed earlier in March.

Further context

Exercising authority under the International Emergency Economic

Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA), President Trump mandated a universal

baseline tariff of 10% on all imported foreign goods (Universal

Tariff), effective from April 5, 2025. In addition, reciprocal

higher tariffs (Reciprocal Tariffs) were also imposed on countries

with which, President Trump argued, the U.S. has the largest trade

deficits these Reciprocal Tariffs were due to take effect from

April 9, 2025. However, in a decision made by President Trump on

April 9, those Reciprocal Tariffs were delayed for a period of 90

days (to the exclusion of China). The Universal Tariffs, on the

other hand, are now in effect. For further information on the IEEPA

and U.S. tariff regime, please see our article ‘Trump’s reciprocal tariff program’

here.

The U.S. has explained that Reciprocal Tariffs represent the

tariff rate deemed necessary to balance the bilateral trade

deficits between the U.S. and its trading partners. The U.S. Trade

Representative indicated that this calculation assumes that

persistent trade deficits are due to a combination of tariff and

non-tariff factors that prevent trade from balancing. It is

understood the Reciprocal Tariffs have been calculated by reference

to the U.S. goods trade deficit with a country. For instance, it

was announced that the U.S. will impose a 34% tariff on China by

reference to a calculated 67% trade deficit that the U.S. has with

China. Notably, the “trade barriers” used to calculate

the Reciprocal Tariffs were not confined to tariffs imposed by each

country. Rather, these trade barriers were assessed by reference to

a wide array of trade measures including value-added tax.

Questions have arisen regarding the countries targeted by

Reciprocal Tariffs. More specifically, Russia, North Korea, Cuba,

and Belarus are not featured. This has been justified on the basis

that these countries already face significant tariffs, and existing

sanctions effectively preclude any meaningful trade with the U.S.

Nevertheless, the U.S. continues to trade significantly more with

Russia than it does with some other jurisdictions that are included

on the list of Reciprocal Tariffs.3

The U.S. tariffs are set to continue in place indefinitely.

Furthermore, the IEEPA order contains a modification authority that

authorizes President Trump to adjust the tariff rate if trading

partners choose to either retaliate or take significant steps to

remedy non-reciprocal trade arrangements and align with U.S.

economic and national security policies.

Retaliation and beyond

Major trading partners of the U.S. continue to grapple with how

best to respond to the seeming breakdown in the global rules-based

trading system that has functioned for many decades. While the

responses appear to have been mixed, as at the date of this

article, the U.S. has indicated that more than 50 world leaders

have sought to engage with the administration to reach a new trade

deal.

Generally speaking, the U.K. Government appears to have adopted

a less confrontational strategy—careful to avoid being

targeted with tariffs for U.S. bound goods higher than 10%. The

U.K. Business and Trade Secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, initiated a

consultation process, inviting businesses to share perspectives on

potential retaliatory measures. He has emphasized that, while the

U.K. remains committed to negotiating a trade deal with the U.S.,

it may consider retaliatory measures if an agreement is not

reached. As part of this consultation, the U.K. published a

400-page indicative list of U.S. goods that could be targeted in a

potential future response.

In Europe, the president of the European Commission, Ursula von

der Leyen, has been highly critical of the tariffs, reiterating

plans to protect EU businesses and noting that the EU is preparing

countermeasures in the event that a trade deal with the U.S. cannot

be reached. In particular, the EU says it has offered the U.S. a

“zero-for-zero” tariff pact for industrial goods. There

is speculation that the EU may invoke its Anti-Coercion Instrument,

which would permit the EU to adopt any measures deemed necessary in

the event of third party “coercion”. Such countermeasures

may include sanctions and tariffs, and they can also target

specific individuals and companies. It is possible that such

countermeasures may include the targeting of U.S. services exported

to Europe in addition to tariffs on goods. The European

Commissioner for Trade and Economic Security, Maros Sefcovic, says

that the EU is “prepared to use every tool in our trade

defense arsenal to protect the EU single market”.

Asian countries are some of the hardest hit by the new U.S.

tariffs. China reacted almost immediately by imposing an equivalent

34% tariff on U.S. imports, to which the U.S. administration

reacted by imposing a 104% tariff on China. On April 9, China

increased its tariff on U.S. imports to 84%. The U.S. has since

imposed a 125% tariff on China. On April 10, China matched this

rate for U.S. imports. As part of its retaliation, China has also

imposed sanctions on the U.S., adding 12 U.S. companies to an

export control list, and six U.S. companies to their unreliable

entity list. More broadly in the region, Vietnam, Indonesia,

Cambodia and India have stated that they will not retaliate.

Likewise, whilst Australia has voiced criticism of the tariffs, it

has indicated that it will not retaliate.

Mexico has stated that, whilst it wants to avoid imposing

Reciprocal Tariffs on U.S. goods, it does not rule it out.

President Claudia Sheinbaum said that her country wants to continue

talks with Washington before taking on any other measures, whilst

also protecting Mexican industries and companies.

The evident challenge for businesses is that the political

context remains highly fluid and unpredictable. Responding to an

environment in which the rules may change on a daily basis makes

any mitigation strategy difficult to effectively design and

implement.

Immediate considerations

Evaluating your supply chains and production

hubs

Tariffs will affect the competitiveness and resilience of

established supply chains in affected sectors. Some will be more

vulnerable than others, particularly where there are multiple

components sourced from different markets. The true impact is

highly business specific. Each supply chain will need to be

assessed to fully determine the impact tariffs and retaliatory

measures will have. The immediate answer for some businesses will

be to onshore or “friend-shore” production, but this will

take time and the benefits of any such moves could be turned on

their head by a change in policy approach. Shifting complex

production facilities, and obtaining local regulatory approvals,

can take many months if not years for some sectors.

Don’t forget the rules of origin

Part of any supply chain (re)assessment will be a detailed

review of the actual origin of products and their components.

Rules of Origin (ROOs) determine the economic nationality of

goods in international trade. The significance of ROOs stems from

their role in the application of tariffs, trade policies, and

import restrictions, and they are a cornerstone of free trade

agreements (FTAs). Applying the relevant tariff rates hinges on

accurately identifying the origin of the goods.

ROOs will be determined under international trade law, but

different rules can be applied via FTAs and across goods. The ROOs

that apply to trade between, for example, the U.S., Mexico, and

Canada under the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) will

be different to those applying to trade between, for example, the

U.S. and Singapore under the U.S./Singapore FTA.

One topical example of how ROOs can play a role is the

automotive sector. According to the U.S. Government, of the 16

million cars bought by Americans in 2024, 50% were imported. Of the

other 50% which were assembled in America, the average domestic

content of each vehicle was around 40%. The question, therefore,

will be which tariffs apply to which components? Or is the tariff

targeting the assembled/finished good? If a good is merely

assembled in a country, is that its true origin for tariff

purposes? What are the consequences if the majority of a good’s

components are manufactured in a third country?

As a result, any assessment of the impact of tariffs, and your

associated mitigation strategy, needs to consider the ROOs in play

and the source of the good in question.

Does the World Trade Organization have a

role?

Not in the near term. The rules-based system of international

trade has been turned on its head. A key component of that system

was the World Trade Organization (WTO), but that has largely been a

moribund body for several years. The fact that the WTO dispute

mechanism is in suspended animation has not stopped Canada and

China from seeing it as a potential route. On April 7, 2025, Canada

initiated a WTO dispute regarding the U.S. tariffs on automobiles

and automobile parts from Canada. According to the WTO, Canada

argues that the tariffs are inconsistent with the obligations the

U.S. has under several provisions of the 1994 General Agreement on

Tariffs and Trade (GATT). China similarly initiated a WTO dispute

on April 8, 2025, on similar grounds.

While tariffs are legally permitted as a trade policy, all WTO

member states, including the U.S., have agreed certain upper limits

on the tariffs they impose, known as “bound rates”.

Further, pursuant to the WTO’s Principles of the Trading

System, WTO member states must observe the most-favored-nation

principle (MFN), which means that apart from certain exceptions,

countries cannot grant one country a “special favor”

without doing the same for all other WTO members.

Violating the MFN principle could potentially lead to a dispute

being brought before the WTO Dispute Settlement System (DSS), as we

have seen with Canada and China. Each country’s request for

consultation with the U.S. under the WTO dispute mechanism argues

that the U.S. has breached the MFN principle and imposed duties in

excess of the bound rates, with disproportionate penalties for

breaches of customs regulations. However, the highest authority

within this system, the WTO Appellate Body, is currently not

functional. This is due to the U.S. persistently blocking the

appointment and reappointment of its members, resulting in the

Appellate Body lacking the necessary quorum to operate. As a

consequence, countries aiming to challenge the legality of U.S.

tariffs through the DSS are likely to face significant practical

difficulties. The absence of a functioning Appellate Body means

that, even if a dispute is initiated, the process may be stalled or

unresolved, making it an arduous task for any nation seeking

redress. The outcome of Canada’s and China’s requests for

consultation is therefore one to watch, but companies should not

plan on the basis that WTO channels can be effectively utilized to

resolve the current crisis in the near term.

Reviewing your contractual risk allocation

Companies impacted by the new tariffs should assess how the

tariffs are addressed (intentionally or otherwise) in their

existing contracts. In the immediate term, exporters to the U.S.

should consider a number of steps including the following:

- Once you are clear on the potential tariffs and associated

rates in play (noting the rules of origin above), and who actually

bears the obligation to pay, review your existing commercial

contracts to determine how the cost of tariffs is addressed (if at

all). - Even if not explicitly addressed, consideration should be given

to whether the imposition of a tariff could be classified as a

force majeure event and/or fall within the scope of any tax

provisions in the agreement. For further discussion of force

majeure clauses, see our article ‘Tariffs and force majeure’ here. - Consider the economic burden of the tariffs and potentially

engage with suppliers, customers, and intermediaries as regards

pricing adjustments or, in the worst case, changes to supplies of

products where it is no longer economically feasible to

continue. - Review termination provisions and associated grounds (alongside

mechanisms for dispute resolution). - Ensure you have robust tariff clauses (and related provisions

such as termination provisions) in your agreements going forward.

These will need to address not just U.S. tariffs but

counter-tariffs from third countries.

Disclosure rules

U.K. and EU listed companies subject to market abuse rules will

need to be mindful of their disclosure obligations with respect to

inside information as part of the market abuse regime. Companies

should consider the test for inside information in this new world

of tariffs, and how this could trigger disclosure requirements, as

follows:

- The information as it relates to the tariffs must directly or

indirectly relate to the company, its shares or any of its

financial instruments, so general information about the tariffs

will not meet this company nexus requirement. - The information must not be generally available—while

information about the tariffs may be generally available, details

of the tariffs’ specific impact on the company may not be

public. - The information must be sufficiently precise—certain of

the tariffs’ economic impacts might have had a realistic

prospect of occurring but, in this context, the information must be

specific enough to enable a conclusion to be drawn about the

possible effect of the tariffs on the company, its shares, or any

of its financial instruments. - If the precise information were to be made public, companies

should assess whether the precise information would likely have a

significant effect on the price of the company’s financial

instruments.

In conducting the above assessment, U.K. and EU listed companies

should consider whether any of their disclosure obligations are

triggered. Boards and management will need to be actively

considering and monitoring this, especially as information

surrounding the tariffs is fast-moving and the situation remains

fluid.

Engagement with governments

Lastly, negotiations around FTAs and tariff deals are conducted

at state-to-state level. It’s therefore critical for businesses

bilaterally or through trade associations to urgently engage with

their governments on the stance to be taken with the U.S., which

sectors may need to be prioritized (and otherwise protected), and

what levels of tariffs are ultimately tolerable. These negotiations

may require governments to lower or even remove their existing

tariff (and non-tariff) barriers for U.S. goods, which may have

ramifications for certain domestic sectors. Trade negotiations

often require difficult trade-offs between domestic sectors.

For those businesses in the U.K., we would encourage you to

engage in the government-led consultation process, which was

launched on April 3, 2025, and closes on May 1, 2025.

Footnotes

1. The tariffs cover the majority of imports, with some

exceptions, including on certain pharmaceuticals and drug

compounds; these exceptions were provided by the White House in a

separate Annex to the Executive Order.

2. The tariffs issued on April 2 and global reactions to

the tariffs may evolve rapidly and unpredictably, with new

requirements potentially taking effect with little or no prior

notice. The information in this article is correct as at the time

of writing, and subject to change as developments

unfold.

3. BBC News, ‘Russia not on Trump’s tariff

list’, April 3, 2025.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.