MALIPO, China — The rural villages of Malipo are a world away from gleaming Chinese cities like Beijing and Shanghai, reached by narrow roads that sometimes skirt dangerously close to deep ravines. Schoolchildren eat simple breakfasts while squatting on sidewalks, and even a local official complained that the remote mountain villages lacked access to the latest 5G internet connection.

But Chinese officials point to overall progress in this thickly forested, highly mountainous border region in southwest China as a reason for their “confidence” in the country’s development model, and in its ability to weather any trade war with the United States.

“We have full confidence and the capability to overcome all difficulties,” Vice Foreign Minister Hua Chunying said last week during a government-sponsored trip to the rural county of Malipo in Yunnan province, on the border with Vietnam.

“As for what the United States is doing, we really don’t want any kind of war, but if we have to face up to reality, then we have no fear at all,” she told reporters at a middle school. “The ordinary people already feel the suffering from the tariff war, so I really hope the [U.S.] administration will come back to normal.”

Hua was speaking before the U.S. and China agreed to slash tariffs on each other’s imports in what Beijing said showed the effectiveness of its resistance against President Donald Trump’s tariff “bullying.”

She and other officials said Malipo, where 233,000 people are spread among several towns and hundreds of “village groups,” is a model for China’s poverty alleviation efforts in recent decades. Per capita disposable income in Malipo was $2,300 a year last year, compared with about $69 a year in 1992.

But Beijing’s professed confidence belies real concern about the work that remains to be done as well as the potential impact of U.S. tariffs as China struggles with structural imbalances and slowing economic growth.

The situation spans China’s urban-rural divide and is obvious even to residents of Malipo.

“The economy is not that good,” said Liu Huixin, a vendor selling processed fruits and other products from Vietnam and Thailand at a market.

“Look at many shops around, people are not buying,” he said.

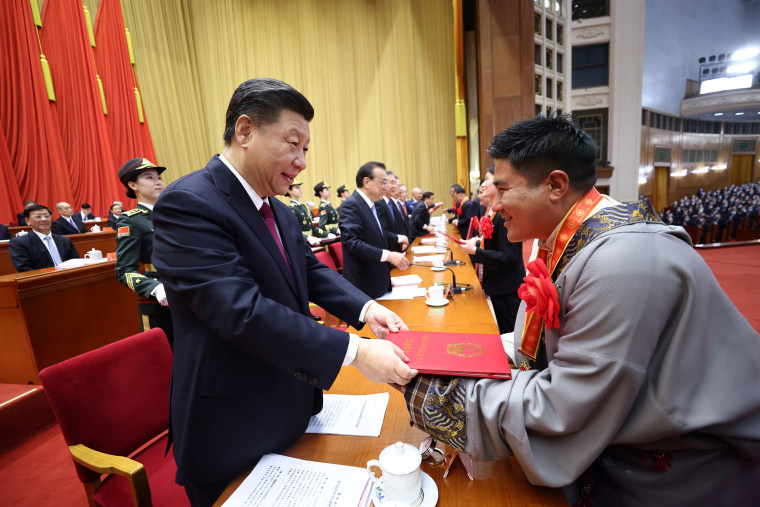

Ending “absolute poverty” — a goal that Chinese President Xi Jinping said was officially achieved at the end of 2020 — is considered essential for reducing income inequality in the world’s second-biggest economy as it strives to catch up with the United States.

More than 450 million of China’s 1.4 billion people live in rural areas, and getting them to spend more on consumer products is crucial as China tries to reduce its economic dependence on exports threatened by tariffs.

China has also touted its “poverty alleviation” program as a model for developing countries in the Global South that face similar challenges.

“The experience of Malipo in poverty alleviation has global significance,” said Liu Guiqing, 40, a senior Chinese diplomat who is also county vice mayor of Malipo under a program that partners central government ministries and wealthy provinces and institutions with impoverished areas.

Hua said the strength of China’s system is its ability to “concentrate resources” on people’s urgent needs. Beijing is thought to have spent hundreds of billions of dollars on poverty alleviation since 2015.

China’s approach to reducing inequality combines “coercive top-down control” with high social spending in an effort to “highlight the perceived failures of liberal free-market capitalism,” Rana Mitter, a historian and political scientist at the Harvard Kennedy School, wrote in a new Foreign Affairs article.

Programs such as the one in Malipo are “an increasingly important part of China’s messaging, that it has development solutions for rural as well as urban areas,” Mitter told NBC News.

“This is likely to be particularly attractive in the many Global South countries that still have large agricultural sectors and may look to Chinese examples to find ways to modernize their own rural area,” he said.

Companies investing in Malipo are still motivated by the “invisible hand of the market forces,” said Jason Choi, director of the Sunwah Group, a Hong Kong-based conglomerate.

He said the improved infrastructure and government support were important factors in the decision by his family’s company to invest about $7 million in a modern tea factory in Malipo, as well as the branding potential associated with Malipo’s ancient tea trees.

“We have created employment directly for more than a hundred people, and for some 10,000 people downstream and upstream,” said Choi, 25.

In nearby Jinping, another county targeted for poverty alleviation, Colorful Group, a company based in the Chinese technology hub of Shenzhen that specializes in graphics cards used in video games, has invested some $15 million in a smart agriculture company and other ventures, creating production jobs for more than 200 people, and for many more engaged in contract farming.

Its corn products are sold in China at Walmart’s Sam’s Club, 7-Eleven shops and on the e-commerce platform JD.com, in addition to being exported to Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

Asked about the impact of the U.S.-China trade war, Malipo Mayor Xiao Changju pointed to the rapid development prospects of border trade with Vietnam and other Southeast Asian nations.

He also echoed a line frequently used by Chinese officials, saying: “We don’t like to fight a trade war, but we are not afraid of one.”