In line with Japan’s annual hiring calendar, Seria Ganeko began job hunting during the tail end of her third year in college. Having been raised and educated on the southern island of Okinawa, she wanted to get out of her comfort zone and challenge herself in a new environment: Mobile phone agencies, sales rep positions and staffing firms were among the nearly two dozen job openings she looked at.

“I explored all kinds of work and industries without limiting myself,” the 24-year-old says. “Regardless of the job type, I focused on companies whose management philosophy I could relate to — places where my effort would lead to meaningful growth.”

She also wanted to improve her English skills. After graduating, she joined the Tokyo branch of a taxi and chauffeur service company in April as a driver, following several months of interning there. The firm offers its employees free weekly English conversation classes with a native instructor, Ganeko says, and with the recent surge in inbound tourism, she often serves international clients — giving her regular opportunities to use English on the job. Having three days off each week was another welcome bonus.

However, things didn’t turn out the way she hoped. Ganeko plans to quit the firm soon and has begun looking for new jobs after struggling with workplace relationships, specifically with her domineering supervisor.

“For my next job, I’m prioritizing an environment with open communication, where it’s easy to consult with others and share concerns,” she says. “Even if the salary isn’t competitive, I’m looking for jobs where I can learn. I want to be versatile and able to adapt flexibly to different situations.”

On a stone for three years — so goes a well-known Japanese proverb, suggesting that even the coldest rock will warm up when you sit on it long enough. It speaks to the value of perseverance, often cited in work contexts to encourage endurance: stick with a job long enough and the results will come. The idea resonated especially well during the era of lifetime employment and seniority-based pay.

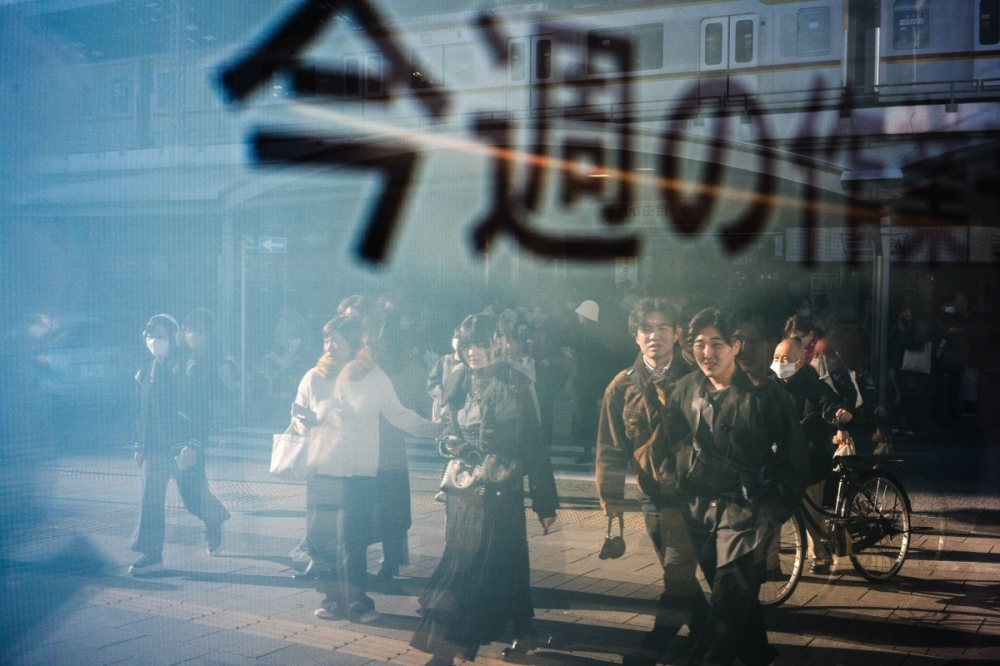

A new generation of Japanese workers, however, no longer see patience as a virtue in the job market. Job-hopping is becoming increasingly frequent among those in their 20s, signaling a clear departure from the country’s long-standing norm of lifetime employment. New workers appear to be reshaping traditional career paths by pursuing broad, transferable skills — while also seeking depth through varied, specialist experiences. The focus is on efficiency and employability rather than loyalty and stability.

Employability vs. loyalty

Japan doesn’t have direct equivalents to Western generational categories like Gen Z, Millennials or Gen X. However, its workforce reflects a generational tapestry shaped by distinct economic and social shifts over recent decades.

During the nation’s period of postwar growth up to the bubble economy, many workers built their careers around lifetime employment, seniority-based pay and a strong dedication to the company — hallmarks of Japan’s traditional employment system.

Following the crash of the asset-price bubble in the early 1990s, a new generation emerged during what came to be known as the “Employment Ice Age” — a period of prolonged economic stagnation and a harsh labor market. Many who came of age during this period, now in their 40s and 50s, struggled to secure stable, full-time positions, often ending up in precarious or nonregular employment. These disrupted career paths have resulted in long-term challenges around job security and financial stability.

In contrast, today’s young workers are entering a market transformed by technology, the gig economy and shifting values that emphasize work-life balance. They often prioritize personal fulfillment and flexibility over traditional company loyalty, says Kaoru Fujii, HR general editor-in-chief at Recruit Co.

“I believe the shift in young people’s attitudes toward work stems from broader changes in social structure,” he says.

“First, from a societal standpoint, Japan is experiencing a declining birthrate and an aging population. As the number of young people shrinks, they’ve become more scarce — and more sought after by companies.”

Fujii’s claims are indeed reflected in statistics. According to a joint survey conducted by the labor and education ministries, the employment rate for March 2025 graduates of universities stood at 98% as of April 1, the second-highest on record (the highest came a year prior) — and this figure doesn’t include part time jobs.

One of the most striking structural shifts has been the reversal of company and career lifespans, Fujii continues. As individuals now face the prospect of working for 60 years or more, they may effectively “outlive” their employers as the average lifespan of a company has shrunk dramatically — falling from around 60 years in the past to just 20 today. This decrease has been driven by waves of restructuring, mergers and acquisitions.

This growing mismatch is reshaping how younger workers think about their futures, prompting a shift toward more sustainable engagement with society beyond the confines of a single employer.

The labor ministry last year released data on the turnover status of new graduates who entered the workforce in April 2021. According to the report, 38.4% of new high school graduates and 34.9% of new university graduates left their jobs within three years — an increase of 1.4 and 2.6 percentage points, respectively, compared to the previous year.

And according to a 2023 report by Recruit Agent based on surveys of users of its recruitment service in 2022, job changes among workers aged 26 and under have doubled compared to 2017, with the gap between younger and older workers widening since 2020. Meanwhile, a Recruit survey on career aspirations revealed that only about 20% of those 26 and under wish to remain with a company until retirement. Another survey targeting job seekers found that many prefer workplaces offering personal fulfillment and opportunities to take on new challenges.

“They essentially want to be generalists who can adapt across roles and industries, yet they also seek to develop skills that make them stand out in any organization,” Fujii says. “This reflects a move away from Japan’s legacy of lifetime employment toward a focus on employability.”

Not everyone is driven by ambition, however. Fujii notes that among workers in their 20s and 30s, common reasons for leaving a company include inability to build a meaningful career or uncertainty about their future after seeing senior employees stuck in the same roles for years.

“Even if they look at their seniors and think, ‘I don’t see a future here,’ they often don’t know what steps to take and end up settling for the status quo,” he says.

“This is exactly what’s meant by ‘quiet quitting,’” he says — referring to a term describing workers doing the bare minimum to meet their job requirements.

Exit and reentry

Back in 2017, Toshiyuki Niino founded Exit — a pioneer in offering services that communicate an employee’s intention to resign to their employer. For ¥20,000 ($140), someone from Exit will quit your job for you. Known as taishoku daikō (roughly, resignation proxy service), similar firms have launched since, offering those who can’t find the courage to quit for one reason or another an easy escape route.

“Since then, the market has expanded,” says Niino. “Back then, resignation services probably still had a somewhat shady image, but now they’re everywhere — like bubble tea shops.”

In fact, nearly a third of young professionals living alone in the Tokyo area said they would consider using a resignation agency to quit their jobs, according to a recent survey by real estate firm FJ Next Holdings. The poll, conducted in February among 400 men and women in their 20s and 30s, found that 6.8% would “definitely” use such a service, while 21.8% said they were “somewhat likely” to.

Niino, who quit three jobs before launching Exit when he was 27, says around 70% of his firm’s clientele are those in their 20s.

“Our client base hasn’t changed much — it’s still mostly people in so-called ‘black’ industries (a term for exploitative workplaces with harsh conditions and long hours), mainly food service, health care and elder care, and construction-related jobs,” he says. “But recently, there’s been a noticeable increase in clients from IT sales and startups.”

Among them, there’s a clear group focused on cost-performance or time efficiency, Niino says — people who aren’t dealing with toxic workplaces or bad relationships but choose to quit because they don’t feel like they’re growing or because there are no senior colleagues they look up to.

“I think, in Japan, quitting a job has become almost like a kind of ritual. Legally, you’re allowed to resign with two weeks’ notice, but in reality, it’s rare for someone to leave cleanly within that time frame,” Niino says.

“People end up tiptoeing around their boss’ mood, getting asked to stay on for at least three more months, training their replacement and making rounds to say goodbye. As a society, I think that whole process is incredibly inefficient.” Thus, Niino says, they turn to resignation agencies such as Exit to make a clean, quick break.

Broadly speaking, Niino says his firm serves two main types of workers. The first group are the quiet quitters who want to do the bare minimum — they’re not interested in growth or purpose, and they have no concern for the company’s vision or what the CEO thinks. For them, work is simply a way to earn money, and they prioritize ease and a comfortable environment.

The second group is made up of young workers in Tokyo striving to succeed in the heart of capitalism — in startups and fast-paced ventures. They also typically fall into two camps: those who chase high pay, even if it means enduring a “black” company, and those who seek purpose and satisfaction in their work.

“In the end,” Niino says, “we get requests from both types.”

Economic pressure

There are many surveys — both government and private — on young people’s attitudes toward work. While results vary depending on the study, certain common trends have emerged that back up Niino’s observations.

“For example, when it comes to how much value young people place on work-life balance, many surveys consistently show that this has become increasingly important,” says Yuki Honda, a professor at the University of Tokyo and an expert on the youth labor market. “However, other surveys reveal a different group of young workers who disregard such concerns — they’re willing to work long hours if it means they can improve their skills. This suggests a polarization is taking place.”

Regionally, there’s a clear difference between urban and rural areas, Honda says. The go-getters are concentrated in major metropolitan areas, while young people in rural regions tend to be more stability-oriented.

“One major driver seems to be economic pressure — many young people simply don’t have enough money,” Honda says.

According to the Cabinet Office’s Public Opinion Survey on Social Awareness from November 2023, the number of people in their 20s and 30s who responded that they “lack financial security or outlook” increased significantly in both 2022 and 2023. Prolonged inflation appears to be a major source of growing financial anxiety among them.

“While skill-building is part of it, there’s a growing sense of urgency: Unless they act, they risk sinking,” Honda says. “That feeling of crisis is becoming more pronounced, though the ability to take action appears split between two extremes.”

Meanwhile, Honda says many young workers are increasingly pushing back against the practice of being randomly assigned to jobs or locations without prior notice — a phenomenon colloquially referred to as haizoku gacha, likened to the randomness of gachapon capsule toy machines.

In response, more companies are adopting so-called job-based hiring, offering clearly defined roles and responsibilities from the start. Unlike Japan’s traditional membership-based model — where employees are hired as general members of the company without set duties before being assigned specific tasks — job-based hiring provides greater transparency and a clearer career path.

“While not yet widespread, some employers now recognize that clarity is essential for attracting younger talent,” she says.

Ganeko, the taxi driver on the hunt for her next job, agrees. “I’d like to know in advance which department I’ll be assigned to — so I can mentally prepare and get ready ahead of time.”

She still has time to decide what path to take next. In university, Ganeko was drawn to the issue of poverty in her native Okinawa and hoped to one day help find a solution.

“I’m thinking about starting my own business someday,” she says. “So I want to learn about children’s education, study how small businesses and their leaders approach management, and gain experience and knowledge that could help me address poverty.”