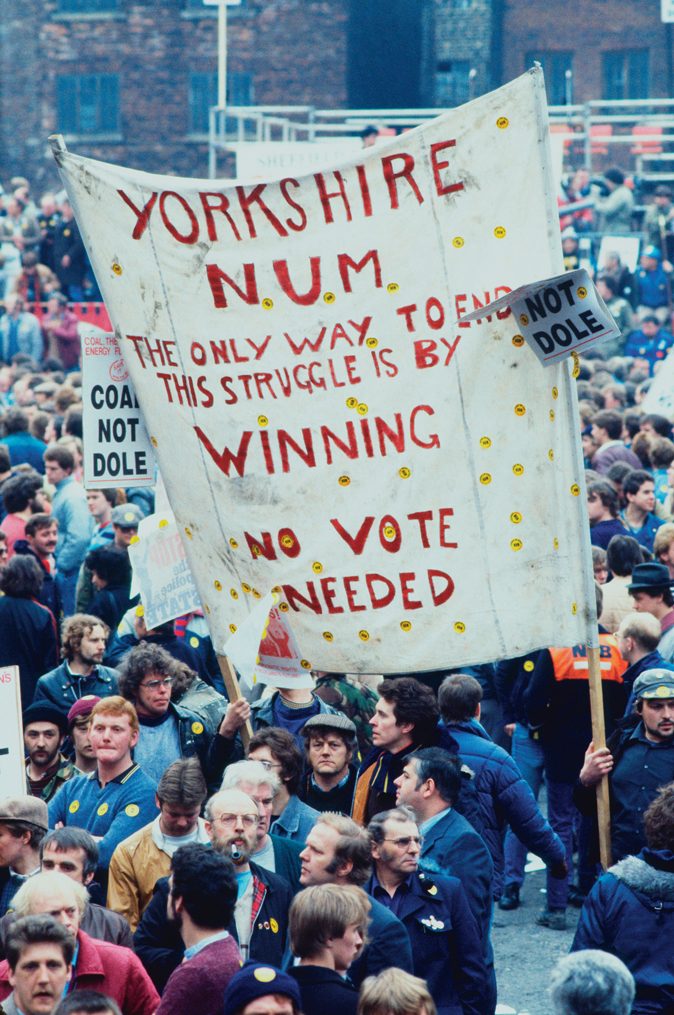

Indeed, the year-long strike between 6 March 1984 and 3 March 1985, during which more than 140,000 miners came out against pit closures, was the most powerful defence of the industry, in the face of those who sought to hasten its demise.

Fifty years ago, young men in the coalfields were invariably directed from the classroom to the pit, for good or ill. However, once there, there were paid apprenticeships and educational programmes, which meant, in the words of one former miner, you could ‘go as far as you wanted to go’, from basic mining certificates all the way to engineering degrees.

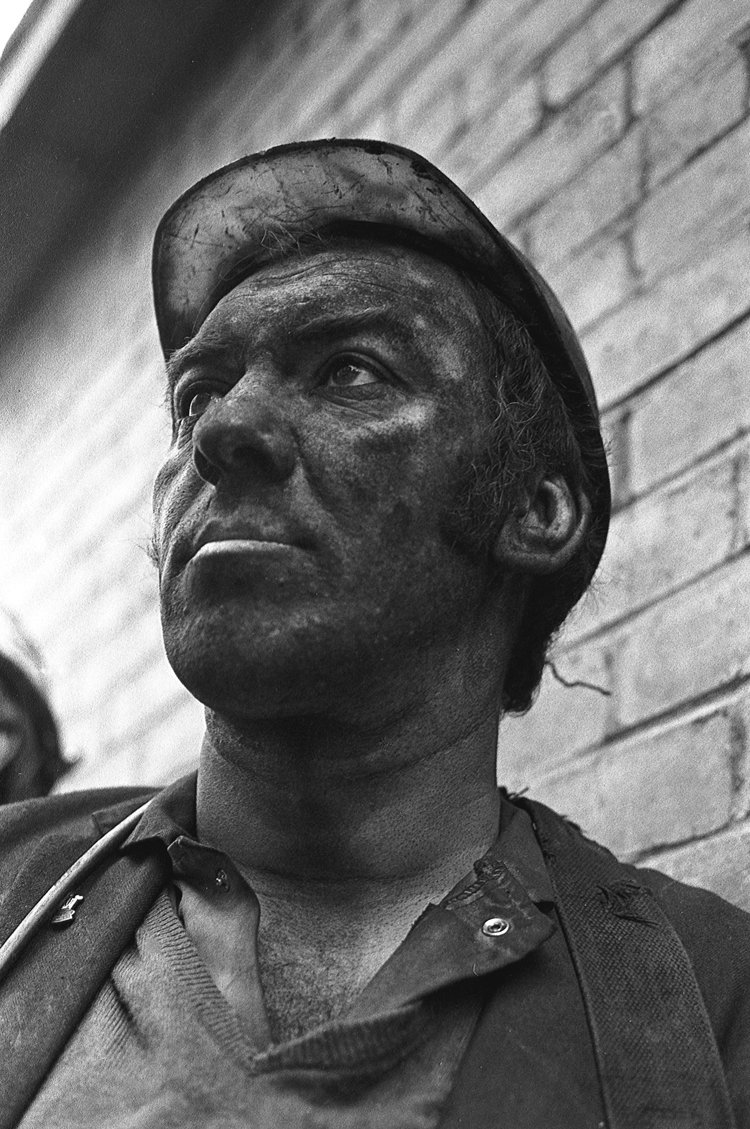

Though promises of a ‘job for life’ were proven woefully hollow by the end of the 20th century, the way in which mining gave its recruits an identity to be proud of had sustained to this day.

Regardless of technical advancements and improved training, mining remained a profoundly risky occupation in the late 20th century. However, the National Union of Mineworkers, which had some 170,000 members in 1981 – staunchly defended the rights of its workers, ensuring their safety was paramount, their pay was fair, and that – if the worst happened – they would be provided for.

Alongside the union, there was also a powerful sense of camaraderie between individual miners, with colleagues trusted to watch each other’s backs and help each other out, no matter what.

One of the postcards sold in support of the strike in 1984 featured a young miner’s son wearing a placard that read: ‘I AM A BIG PART IN THIS STRIKE IT’S MY FUTURE.’ At the end of our interviews, men often reflected on their feelings as to whether they would have been happy for their sons and grandsons to have gone down the pit, a future that had been denied to them.

While some were relieved that young men no longer had to work in such grim conditions, many felt that the progress in workers’ rights that had been made over generations had been lost.

One former Yorkshire miner told me how his own son, despite his best efforts, had only been able to get a zero-hours contract, and spent his days sat at home waiting for a text message to confirm whether he was wanted or not. This situation seemed little different to that my own great grandfather faced 100 years earlier, standing at Liverpool’s dock gates to see if he would be chosen for work, or be sent home with empty pockets and a hungry belly.

According to the Living Wage Foundation, in 2023 more than six million people in the UK were trapped in precarious forms of work, without the regular hours needed to live their lives with any degree of certainty. Young people are the worst affected, with the Trades Union Congress (TUC) finding almost half a million workers aged between 16 and 24 employed on a zero-hours contract in 2024.

Reading of practices in some workplaces today, it often feels like we are living in a new Dickensian age. However, unlike the 19th century, they are now monitored by the all-seeing eye of technology, with workers dismissed by algorithm or convicted for theft because of faulty software.

Many of the former miners I spoke to attributed the erosion of workers’ rights to the loss of the strike 40 years ago. It was hard to argue with them: just last year the Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported that levels of poverty were around 50% higher than they were in the 1970s; the upward trend having begun under Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government.

Poignantly, poverty rates were particularly high in former mining communities, where well paid jobs in industry had been replaced with low-paid, insecure work.

According to the latest State of the Coalfields report, warehousing now employs more than 175,000 people in Britain’s former coalfields, a number almost equal to the size of the workforce employed in the coal industry before the 1984-85 strike.

These so-called ‘fulfilment centres’ often offer their workers anything but. Reports abound of trade union suppression and, unlike the pit, there seems to be little time for conversation or anything resembling camaraderie.

Even bleaker are stories of employees being penalised for sickness, or soiling themselves on the shop floor as they could not afford the time lost going to the toilet. It seems the risks of injury are also far higher than we might expect above ground in the 21st century. Last summer The Observer revealed that ambulances were called out to Amazon’s UK warehouses 1,400 times in just five years.

In the autumn, Labour unveiled its Employment Rights Bill. It is the first step in a ‘Plan to Make Work Pay’, with an ambitious tranche of employment reforms, including day-one rights, greater protection against harassment, tighter regulation of fire and rehire and an end to zero-hours contracts.

The bill will also repeal restrictions previously introduced on the process for trade union recognition, and strike action. Undoubtedly it is a step in the right direction, but only time will tell if they can begin to build back everything that has been lost since the pit wheels stopped turning.

In the meantime, if we want to restore dignity back to labour, looking for inspiration in the darkness of the coal mine may not be a bad place to start.

Mining Men: Britain’s Last Kings of the Coalface by Emily P Webber is out on 13 February (Vintage, £22). You can buy it from the Big Issue shop on bookshop.org, which helps to support Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Do you have a story to tell or opinions to share about this? Get in touch and tell us more. Big Issue exists to give homeless and marginalised people the opportunity to earn an income. To support our work buy a copy of the magazine or get the app from the App Store or Google Play.