India has a problem with its innovation funding: it knows what works but hesitates to scale it up.

The Department of Science and Technology’s (DST) NIDHI programme stands as one of the government’s most successful science and technology initiatives. Since its 2016 launch, it has supported over 12,000 startups through more than 175 incubation centres across the country, creating over 130,000 jobs and 1,100 intellectual property (IP) assets.

Success stories include ideaForge (India’s leading unmanned aerial vehicle manufacturer), Atomberg (the innovative consumer appliances maker known for energy-efficient BLDC fans), and Ather (the electric scooter manufacturer).

Yet after nine years of proven results, NIDHI’s grant amounts remain frozen — Rs 10 lakh for the NIDHI Promoting and Accelerating Young and Aspiring Innovators and Startups (PRAYAS) programme and Rs 30,000 monthly for the NIDHI Entrepreneur in Residence (EIR) programme.

Before NIDHI, there was the trailblazing Biotechnology Ignition Grant (BIG), launched by the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC), an entity set up by the Department of Biotechnology (DBT) in 2012.

Receiving over 12,000 applications, the BIG grant has supported more than 950 companies, spurring the creation of over 125 products and over 500 IP assets.

Among the many companies it has supported is PadCare, which developed the world’s first sanitary pad recycling technology, popularised by the startup’s successful appearance on the business reality show Shark Tank.

BIG has been such a pioneer that many subsequent government schemes have been modelled on it.

However, just like NIDHI, BIG’s once-impressive grant amount of up to Rs 50 lakh for 18 months — the only grant at the time that gave anywhere close to the United States’s (US) Small Business Research Innovation, phase-one grant of about $100,000 (roughly Rs 85 lakh) for proof of concept — has remained at that level 13 years on.

Not only have the NIDHI and BIG grant amounts stagnated despite their success, but both programmes have especially suffered in the last 18 months due to administrative reasons.

The reluctance to scale success while tolerating ineffective schemes elsewhere risks restraining India’s science and technology-based innovation from flourishing, particularly at a time when the country is determined to move in line with its strategic philosophies of Make in India, Aatmanirbhar Bharat, and Viksit Bharat 2047.

The NIDHI Success Formula

“My limited understanding is that every successful SIIC (Startup Incubation and Innovation Centre, Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur) startup was a NIDHI grantee,” says Professor Amitabha Bandyopadhyay of IIT Kanpur, who was until recently leading innovation and entrepreneurship activities at the institute.

What makes NIDHI work? The answer lies in a fundamentally different design philosophy that enlists incubators as partners, empowering them with both funding and autonomy.

“One of the things that NIDHI has done well is it has relied on a network of incubators and other such entities to scale up the activities. And that has a sort of multiplying effect because then you’re not centralising things,” explains Premnath Venugopalan, Director of Venture Center, India’s largest technology incubator hosted by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research’s (CSIR) National Chemical Laboratory in Pune. Venture Center is the national implementation partner for the NIDHI EIR scheme, one of several that fall under the NIDHI umbrella.

“After all, somebody has to scout for candidates, make sure that they’re the best candidates to support, grow them, and so on. That is important,” he adds, noting that the use of incubators also “increases speed and efficiency, which plagues some other programmes sometimes.”

This distributed approach transforms the funding dynamic entirely. Instead of entrepreneurs navigating distant bureaucracies, they work with incubators staffed by people who possess relevant knowledge, techniques, and experience in innovation and entrepreneurship.

Unlike centralised programmes that slacken decision-making in Delhi, NIDHI routes grants through incubator networks. Even BIG, unlike other BIRAC programmes, is executed by BIG partners, eight of them, among which are Venture Center and SIIC, IIT Kanpur.

The IIT Kanpur incubator is associated with the NIDHI programme, and Prof Bandyopadhyay has been a close witness to this collaborative work for many years. “NIDHI would simply transfer Rs 1 crore to IIT Kanpur and say that you give it to whomever you please, at a maximum of Rs 10 lakh per person. Now because the money comes to IIT Kanpur, the institute would advertise, saying we have got the NIDHI money, and whoever wants it can apply. From giving out the advertisement to the person getting the money, it would be no more than one and a half to two months,” Prof Bandyopadhyay explains.

“That is the beauty of the NIDHI scheme,” he adds. “It is entirely at the discretion of the incubator. Therefore, the whole thing is much faster.”

That’s not all. NIDHI’s strength also lies in how funding flows through the schemes. “One of the USPs of this programme is the continuity in the scheme in terms of going from fellowships (EIR) to PRAYAS, which is a prototyping grant, to seed funds,” Premnath says.

The NIDHI programme constitutes five schemes: NIDHI EIR, NIDHI PRAYAS, NIDHI Seed Support System (SSS), NIDHI Centres of Excellence (CoE), and NIDHI Accelerator.

NIDHI PRAYAS, for instance, helps innovators who have an idea on paper and are seeking guidance and funding to take this idea out of the paper and onto a prototype. NIDHI EIR is like a fellowship for budding entrepreneurs who want to flesh out their ideas further and advance through the prototyping stage.

Additionally, there are the NIDHI Technology Business Incubators (TBI) and NIDHI Inclusive Technology Business Incubators (iTBI) schemes, targeted more directly at incubators than at startups, but the goal ultimately is to benefit the latter.

These schemes together support entrepreneurs and startups at various stages in their journey, covering the entire continuum of knowledge creation, technology development and its applications, and ecosystem building.

Although BIRAC’s BIG doesn’t offer such wide coverage, the agency has a fairly good spread too. “BIRAC has also done fellowships; there’s something called the SIIP (Social Innovation Immersion Program) fellowship. Then there’s BIG. There’s SBRI (Small Business Innovation Research Initiative), and there’s BIPP (Biotechnology Industry Partnership Programme). Then there are seed funds called SEED (Sustainable Entrepreneurship and Enterprise Development Fund) and LEAP (Launching Entrepreneurial Driven Affordable Products Fund). And there is a fund of funds called AcE (Accelerating Entrepreneurs). So they have a fairly good spectrum of funding for biotech, biomed,” Premnath explains.

But since the NIDHI programme falls under DST, any innovation based on science and technology could be considered by it, in contrast with sector-specific schemes put out by focused departments like biotechnology, space, and atomic energy. This gives NIDHI the power to make a wider impact on innovation across science and technology.

Entrepreneurs who have accessed NIDHI funding consistently praise its support and efficiency relative to other schemes. Shaivee Malik, co-founder of Yotuh Energy, is among them. Her company manufactures electric air-conditioning systems for refrigerated vehicles — a niche but growing market as logistics companies seek cleaner cold transportation solutions.

Yotuh is a double NIDHI grantee, and Malik credits the programme with keeping her venture going during its initial stages. “Initially, we took some support from our family. But after that, it was government grants that helped us. We started with the NIDHI EIR grant. Every month they would give us Rs 30,000. It is a total Rs 360,000 grant, which comes for one year. And that really helped us, at least to make some small prototypes,” she says.

She subsequently received the Rs 10 lakh NIDHI PRAYAS grant. The NIDHI grants provided a crucial runway until Yotuh could raise funds to grow the business, especially when other grants from different ministries were not as effective. “There was one grant which we applied for in 2023, and it’s 2025, and we still haven’t got the second tranche of the grant. We had submitted our documents long back. It’s still in the process, they say,” Malik says.

Importantly for cash-strapped entrepreneurs, the NIDHI EIR and PRAYAS and the BIG grants come without equity requirements. “It’s valuable that you’re getting equity-free capital to accelerate R&D (research and development). In that sense, it’s very useful. And the incubator also tends to be very supportive,” says an early-20s deep tech founder who did not want to be named and is being mentored by a top biotech incubator that is a partner to both the NIDHI and BIG schemes.

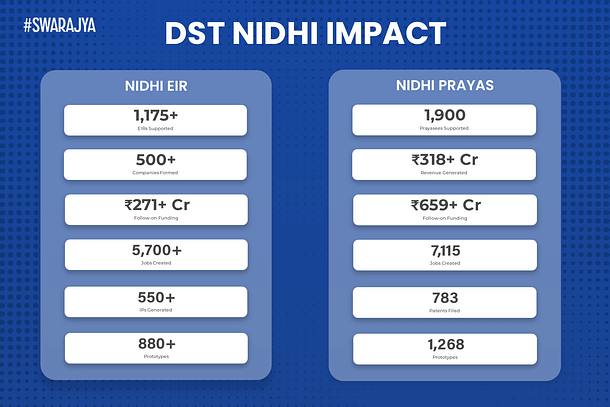

The DST NIDHI programmes have made an excellent impact on early-stage innovation in India

Systemic Challenges

Despite the successes of these programmes, young entrepreneurs report facing challenges with the grants process.

“A challenge with these grants is the amount of documentation required,” says this founder, acknowledging that the elaborate documentation may be a function of the government’s need to exercise caution while using taxpayer money.

But that doesn’t make the process any less annoying. “It’s very frustrating because when you’re doing early-stage R&D, you have some unexpected expenses which you did not show in the initial proposal. And they’ve told you that you can only spend 30 per cent of the grant on some X activities. Now if you end up spending more on it, it becomes an entire process to demonstrate why you had to do it. So there’s a lot of documentation work that needs to happen before the grant,” she says.

The documentation work persists even after the receipt of the grants. There tends to be a review every few months — the grants are disbursed in tranches, tied to the achievement of pre-decided milestones. And then, at the end of the grant period, more documentation follows.

The young pioneer was also frustrated with the application process: “Just the UX (user experience) for the application on the website was so hard. If you had to modify something, everything you entered before that would get deleted.”

This founder’s challenges persisted right through to the end. “Even during the technical evaluation panel (the final round of the process), I noticed that the panellists did not really seem to have, in spite of the fact that so much documentation had been submitted earlier, any actual idea of what the project being proposed was. These people were asking extremely basic questions about the fundamental stuff itself, which had already been either mentioned in the proposal or in the presentation that I’d given on the same day. I think that was very disappointing,” she says about a review process that is otherwise widely appreciated for the constructive feedback it presents to startups.

It also took this entrepreneur close to a year to learn that they had not won the BIG grant. “When you are trying to get into entrepreneurship,” says Prof Bandyopadhyay, “you are not pursuing a career with a stable job. So time is money. Therefore, the speed at which you get the money is important not only for your survival, but also the idea can get stale. In the entrepreneurship or innovation ecosystem, ideas get stale in months.”

BIG’s application success rate is also lower compared to global standards. “The success rate is somewhere close to 5 per cent. A thousand people apply, and you get 50 grants. The general rule of thumb internationally is that you should try and design for 10-15 per cent success rates so that people are not too disappointed,” Premnath explains, noting that the BIG success rate was around 15 per cent in its initial years.

Beyond these systemic struggles, the innovation funding landscape faces broader challenges that have affected programmes across departments of late. Flagship programmes like NIDHI and BIG have experienced significant delays over the past 18 months due to administrative restructuring.

In BIG’s case, the scheme had been on track all these years. Every six months or so, a call for proposals would go out, and the funding upon selection of grantees would be released within roughly seven or eight months of the call going out. However, in the last year, the call has gone silent. The last call for proposals was announced on 15 April 2024. The call before that had gone out on 1 July 2023.

This delay has stemmed from two primary factors: new cabinet approvals required for these programmes after the election and the government’s decision to route funding through the Public Financial Management System (PFMS).

It’s not just BIG; even NIDHI has suffered a delay on account of these factors. “Even DST programmes have gone for new cabinet approvals. The NIDHI programme as well. So you would notice that the last time the EIR and PRAYAS ran — there’s a gap of about 18 months almost,” Premnath notes.

The PFMS transition, while intended to improve financial oversight by ensuring grant money doesn’t sit idle with recipients, has caused delays across multiple departments.

But similar delays have occurred in the past as well. “The timing has not been predictable for the disbursement of funds. Earlier, the funds would go as cheques, then the transfers became digital, then they changed the whole system around. In all this transition, the timing of the funds has always been a question,” says a committee member in a department of the Ministry of Science and Technology who did not want to be named.

“But this delay is only a transient thing,” Premnath assures, expecting “things will accelerate considerably in the coming few months because now all the cabinet approvals have been secured by those departments,” adding, “I also know that they are rolling out slightly revised schemes.”

The Stagnation Paradox

What’s puzzling about India’s innovation funding landscape is that successful programmes haven’t been scaled up proportionally to their demonstrated impact.

“I know that the NIDHI schemes received a very good review; the impact shown was very high. Just to give you a ballpark number, if Rs 100 crore were invested, the valuation of companies formed would be worth more than Rs 5,000 crore. And this is only six or seven years down the line. So if you see that kind of value addition, why shouldn’t you scale it up?” Prof Bandyopadhyay asks.

That kind of success should trigger programme expansion. Instead, funding levels have remained static, in the case of NIDHI for nearly a decade and in the case of BIG, for well over it.

A biotech company founder who did not want to be named said they received the Rs 50 lakh BIG grant in 2019. It sufficed back then since they were just a team of two, and all they were doing was product development. “It was like kicking off, developing a proof of concept (POC). But if you ask me now, at this stage, Rs 50 lakh is peanuts. The quote that we got way back in 2020-21 for a 400-patient clinical trial was more than Rs 50 lakh. So it wouldn’t suffice for anybody who’s in the after-POC stage of product development,” the entrepreneur says.

Premnath indicates change may be coming, at least for NIDHI: “There is a move to increase it. That is already in the works. There was a review of the programmes. And the government has already taken note of it, and my understanding is it will be rolled out very soon. But those numbers have been upgraded, and I think it’s awaiting some final approvals.”

The committee member in the Science and Technology Ministry suggests that the sobre utilisation of grant funds over the years may have prompted the stagnation. “If you look at the utilisation of the funding, I wouldn’t say it’s overshot always. So maybe the demand is not as high. And hence the need to push up the funds may not be there,” he says.

The underreporting of fund utilisation may also be a problem. “It (the reporting) will always go back as inputs for their (the department’s) next plan. How much is used and what has been the output of all that funding doesn’t always reach the department in helping them to get more funds,” he explains.

The industry veteran who is now assisting the government with innovation efforts also points to the low application success rate, as Premnath did earlier. “Out of 75 applications, the average that gets cleared is around five or six, or maximum eight,” he says.

However, he attributes it to the quality of innovation coming in for consideration. “We find most of the time the definition of innovation is not clearly understood,” the commitee member says, noting that the steering committee, which evaluates the proposals, may look at what qualifies as innovation differently from those who are typically applying for government grants.

“Ninety per cent-plus are people from government academic institutions who are on a senior level — the Deans, the HODs (heads of department), and so on. And they come with say 20-plus years of experience or so. Their outlook to innovation is different from what a startup or a private company would actually be looking at,” he says.

Sometimes, the level of innovation may suffer because the universities might apply for grants under pressure to secure grant funding.

The question the department faces is: Is this project innovative enough to be funded? And the answer is not always easy because innovation is subjective. The committee member has proposed laying down what qualifies as good translational research and sharing this information with innovators in advance in the form of, say, a downloadable document on the website. “That education is very important,” he asserts.

It’s important because, in his view, the innovators often do not understand the market requirements well enough. “That business acumen or product viability when they are doing innovation, we have seen it to be a big gap,” he says, adding, “The innovators are extremely good in what they are doing. How much would that be useful for the market, or relevant, they probably are not able to estimate it well.”

According to Premnath, there are fundamental misconceptions about how science and technology funding should work. “When you fund research, it should not be equated to an investment in a production facility… You’re actually encouraging failures because you want people to dare to take risks,” he explains.

The innovation ecosystem benefits — the development of skilled talent, knowledge spillovers, supplier networks, investor interest, and wider cultural shifts towards entrepreneurship — generate value far beyond what any individual company might return through direct returns.

“So, for example, if the US government puts in money in research, and you calculate what came out of it in terms of, say, income from tech transfer or whatever it is, that will be minuscule. But you can see what impact it does in society around you, in terms of the Boston area or Silicon Valley. That is diffusional. You can’t quantify it easily, but it’s very large, and you know that’s happening,” Premnath says.

The use of straightforward cost-benefit analyses, employed in other government sectors, to determine grant funding levels in science and technology will not work. Nor will the view, held by some, that giving grants makes people lazy. Science-based ideas are to be thought out differently.

The greater the funding in science and technology, the wider the pipeline will be. “Many will fail, but you want to have as much pipeline as possible because it’s a funnel at the end of the day. Only so many will succeed at the end, but you need to have a large funnel,” says Premnath, in whose view the pipeline in India needs to be 10 times bigger than it is now.

The benefit of a wider pipeline will be the larger pool of candidates going down the conveyor belt of innovation for venture capitalists to invest in and for many more success stories to be churned out.

Ultimately, government support for startups has to be to the extent that they become worthy of investment, either by investors, customers, or other stakeholders. Government funding should be sufficient to attract external funding and not necessarily so much that it substitutes for it. In that sense, what’s required is catalytic funding.

According to Premnath, not only should the grant amounts be higher, they ought to be 100 per cent grants without any kind of equity arrangements. “The idea is to sweeten the deal for investors. It is not to necessarily get a return immediately from it. What is a government going to do with equity return anyway? They will get much more in taxes; they will get much more in people who are employed and their income tax and service tax, GST (goods and services tax), all of those things, and continuously for many years from those companies that succeed,” he argues.

According to the committee member in the Science and Technology Ministry, it would help if the government doubled down on specific areas of focus, as well as related schemes and programmes, so that a better precedent could be set for innovative research work. “The focus can be on a few things in-depth. Identify one or two areas and then see how we can go intense into those and how we reward, recognise, and then promote such innovation so that there is enough clarity with people as to what kind of innovation they can get into and what would be possible for them to get good funds and how they can make use of it.”

Currently, there are far too many innovation programmes running with widely varying focuses and timelines, and with not enough people to manage all the different programmes efficiently.

A glimpse from the National Technology Week 2023

The Deep Tech Funding Gap

The grants provided by the NIDHI, BIG, and other similar schemes are especially insufficient for hardware and deep technology (tech) companies requiring extensive research and development (R&D) investment.

Within NIDHI, for instance, between PRAYAS, which is a Rs 10 lakh grant, and the seed funding scheme offering up to Rs 1 crore, there is a huge funding gap. “Just to compare, the US’s phase one grant is $100,000 (roughly Rs 85 lakh). And it’s a no-strings grant. The reason the number (the grant funding) needs to be high is to attract people to those high-risk domains. Otherwise, they will not do high-risk work. They will only do some tinkering around,” Premnath explains.

This funding gap becomes particularly pronounced in what Premnath identifies as the Rs 2-4 crore range: “Venture capital funders want to come in, say, at $1 million, which is Rs 8 or 9 crore. If it’s too small, they won’t be keen. The seed funds today from the government stop at about Rs 1 crore (Rs 1 crore is given on an exceptional basis)… So if you’re looking at the Rs 2-4 crore range, if you get one angel investor and one seed fund, you still cannot make up that gap.”

Professor Bandyopadhyay, who has mentored many entrepreneurs over several years, articulates this challenge for hardware startups: “If you are making a hardware product, to take it to the market, you will need a production unit. Production unit meaning you have to install certain high-throughput machines. You have to have some land or real estate for that, either on rent or lease or purchase. You have to now recruit people on the production line, on finance and accounts, and on marketing. So with anything below Rs 10 crore, you cannot imagine starting a production line. And I am being very conservative. The government does not have any scheme that will give such an amount.”

If deep tech innovation is to be encouraged in India, especially in the high-risk, high-reward sectors, grant funding has to be increased to levels adequate to support such ‘road less travelled’ R&D work.

Lessons From Global Peers

Countries with similar technological ambitions as India have designed innovation funding systems that adapt to market realities and scale successful approaches.

Israel, for example, is known to regularly adjust its funding programmes to match market realities. The country’s famous “Yozma” programme transformed Israel’s venture capital landscape by using government funds as a catalyst rather than a controller, providing matching funds to private investors while limiting the government’s equity stake.

Israel addresses the “valley of death” that Indian startups face after initial government funding by providing graduated funding tiers that grow substantially as startups advance, with later-stage grants running into millions of dollars, recognising the escalating costs of bringing hardware and deep-tech innovations to market.

While the grants in Singapore, ranging from S$250,000 to S$500,000, are substantial, what really makes the country’s Startup SG Tech programme effective is its implementation efficiency. The streamlined processes and minimal bureaucracy are widely appreciated by entrepreneurs.

Singapore’s strength speaks to Premnath’s point about process efficiency: “With the money flow, the general rule is the government has to figure out ways by which the processes are streamlined, such that it flows faster with minimum decision points in between. The more the number of decision points, the more the number of audits and cross checks and so on; it either slows down the process or increases the risk in the process. When I say risk, it also means you don’t know what’s coming next. Normally, you want predictability in the process.”

Successful international models also emphasise globalisation support — particularly relevant for deep tech companies. “In Europe, in smaller countries where they rely on export markets, like Sweden, there’s a lot of focus on internationalisation. They support the startups to go global,” Premnath notes. “So does Israel. So for them, when they think, they think global, right from day one.”

India’s pharmaceutical industry is an interesting case in point. While holding a small share of the global market by value, it plays an outsized role in global medicine supply, particularly in generics and vaccines. The industry’s success is heavily reliant on exports, which drive growth and attract investments.

“In pharma — and India does generic pharma — we say that we supply every third medicine in the world. But if you look at the Indian market size, it is hardly a single-digit percentage — 3 per cent — of the global market. But our industry is larger because it supplies all over the world. So the domestic market is small, but it would not thrive as much if it did not look at export markets. And it wouldn’t attract investments either,” Premnath explains.

Simply put, ‘Make in India for the world’ must be embedded deeply into India’s innovation vision and plans.

India’s journey towards technological self-reliance depends critically on the effectiveness of its science and technology funding mechanisms. Programmes like NIDHI stand as compelling evidence that well-designed government initiatives can catalyse innovation.

Yet the reluctance to scale such successful programmes, coupled with persistent process and implementation challenges, threatens to hold India back from innovating to its true potential, and at a time when that is India’s calling.

The path forward for India requires scaling what works, reimagining what doesn’t, eliminating unnecessary barriers, and creating predictable processes so that innovation can thrive unabashedly.